Paved Surfaces Can Foster Build-up of Polluted Air

New research focusing on the Houston area suggests that widespread urban development alters wind patterns in a way that can make it easier for pollutants to build up during warm summer weather instead of being blown out to sea.

The international study, led by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), could have implications for the air quality of fast-growing coastal cities in the United States and other mid-latitude regions overseas. The reason: The proliferation of strip malls, subdivisions, and other paved areas may interfere with breezes needed to clear away smog and other pollution.

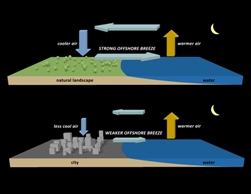

The research team combined extensive atmospheric measurements with computer simulations to examine the affect of pavement on breezes in Houston. They found that, because pavement soaks up heat and keeps land areas relatively warm overnight, the contrast between land and sea temperatures is reduced during the summer. This in turn reduces nighttime winds.

In addition, structures interfere with local winds and contribute to relatively stagnant afternoon weather conditions.

“The developed area of Houston has a major impact on local air pollution,” said NCAR scientist Fei Chen, lead author of the new study. “If the city continues to expand, it’s going to make the winds even weaker in the summertime, and that will make air pollution much worse.”

While cautioning that more work is needed to better understand the impact of urban development on wind patterns, Chen said the research can eventually help forecasters improve projections of major pollution events. Policymakers might also consider new approaches to development as cities work to clean up unhealthy air.

Houston, known for its mix of petrochemical facilities, sprawling suburbs, and traffic jams that stretch for miles, has some of the highest levels of ground-level ozone and other air pollutants in the United States. State and federal officials have long worked to regulate emissions from factories and motor vehicles in an effort to improve air quality.

The new study suggests that focusing on the city’s development patterns and adding to its already extensive park system could provide air quality benefits as well.

“If you made the city greener and created lakes and ponds, then you probably would have less air pollution even if emissions stayed the same,” Chen explains. “The nighttime temperatures over the city would be lower and winds would become stronger, blowing the pollution out to the Gulf.”

Chen adds that more research is needed to determine whether paved areas are having a similar effect in other cities in the midlatitudes where sea breezes are strongest. Coastal cities from Los Angeles to Shanghai are striving to reduce air pollution levels. However, because each city’s topography and climatology is different, it remains uncertain whether expanses of pavement are significantly affecting wind patterns.