New Water in the Desert

Tucson's drive for a new supply took a U-turn

Tucson Water learned critical lessons about water treatment decision-making, customer communication, and public involvement in its first attempt to take its then-500,000 customers from groundwater dependence to surface water supply. The water department is the largest municipal provider in southern Arizona. It applied those lessons in a second attempt that succeeded and soon will be expanded.

Tucson Water learned critical lessons about water treatment decision-making, customer communication, and public involvement in its first attempt to take its then-500,000 customers from groundwater dependence to surface water supply. The water department is the largest municipal provider in southern Arizona. It applied those lessons in a second attempt that succeeded and soon will be expanded.

The city sits at the northern boundary of the Sonoran Desert. It has no permanent surface water sources and only 11 inches of annual rainfall. Since the late 1800s, the region has mined groundwater for its drinking water, but overpumping gradually de-watered the aquifers. The water table in some areas dropped more than 250 feet from the late 1940s to 2001. Click here for a map of the Central Avra Valley Storage and Recovery Project.

Since the late 1970s, the city had been pursuing water from the Colorado River to augment its water supply. The state of Arizona and the U. S. Bureau of Reclamation built the Central Arizona Project (CAP) canal system to move river water into central and southern areas facing groundwater depletion. During that time, the city entered into a multi-year series of negotiations and discussions with the state and the U. S. Department of the Interior to determine the size of Tucson’s allocation of CAP water. In 1984, Tucson’s annual allocation was set at slightly more than 148,000 acre-feet, which has been reduced to approximately 144,000 through a number of agreements with other regional water providers. The allocation was based on the projected service area population in the year 2034.

Tucson Water and its customers invested more than $150 million for a CAP water treatment plant, as well as new reservoirs and transmission mains to move the treated water from the plant into the drinking water distribution system. The treatment process included primary disinfection with ozone, coagulation and flocculation, anthracite coal filtration, and secondary disinfection with chloramine. The selection of ozone and chloramine was made in light of community concerns over disinfection byproducts.

Recharge and Recovery: A Primer

When you think of large-scale water filtration and storage, what images come to mind? In most cases, filtration conjures the image of large facilities where water flows through carbon, coal, sand or even plastic membranes to remove suspended or dissolved materials. Storage occurs in surface water reservoirs. In Tucson, another image springs to mind – recharge basins and groundwater recovery wells.

What is Recharge?

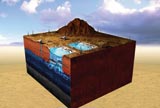

Recharge refers to the replenishment of an aquifer's groundwater. An aquifer is a layer of underground sands, gravels and silts where water collects. Natural recharge takes place when rainfall, stream flow, or melting snow percolate into the ground and are stored in these layers. Tucson Water replicates this same process to filter and store its Colorado River water.

Tucson has selected basin recharge as both a filtration and storage system for its supply of Colorado River water delivered to the region via the Central Arizona Project (CAP) canal system. Tucson Water recovers the blend of recharged river water and groundwater through a number of groundwater production wells in the vicinity of the recharge basins.

Recharge: Filtration the Natural Way

Intentionally filtering water through sand to remove suspended materials is a practice that dates back thousands of years. Historians have found descriptions of sand filters written in documents dating back 4,000 years. By the 18th Century, sand filtration had become the water purification method of choice in much of Europe. Sand filtration is still a technology in use today in many treatment plants.

By the mid-20th Century, scientists began to examine more closely the impact of the recharge process on microorganisms and other organic compounds in the water supply. In addition to physically filtering out many microorganisms, including bacteria and viruses, researchers discovered that naturally occurring biological activity in the first few inches of soil dramatically reduces the total organic content of the water as it recharges into the ground.

At Tucson Water’s Clearwater facility, the combination of physical and biological filtration provides very thorough "cleansing" of the recharged Colorado River water. Approximately 50 percent of the organic material in the river water is removed. This allows the use of chlorine as a residual disinfectant in the recovered water without creating a high level of disinfection byproducts. By contrast, high organic content in surface water supplies is forcing many water utilities to move to alternative disinfection strategies such as UV or chloramines to minimize disinfection byproducts.

Taking Advantage of Nature’s Bank Vault

The second primary advantage of recharge and recovery is that it makes use of the vast storage capacity available in the aquifer. Recharge allows the city to store additional supplies of Colorado River water in the local aquifer, where they will remain until needed in the future. The city’s Clearwater facility is currently recharging 90,000 acre-feet each year, but only 60,000 acre-feet are recovered for delivery to customers. The remaining 30,000 acre-feet are stored in the ground and become part of the city’s future groundwater resources. The evaporation rate from the recharge basins – about 1.5 percent – is vastly less than occurs at a typical surface reservoir.

Worth a Look

Many communities are looking seriously at using these methods to make better use of wastewater effluent, as well as capture seasonally available water supplies for use during dry periods. While water filtration plants may always be the treatment method of choice for most water providers, recharge and recovery facilities offer many advantages that should at least be evaluated as part of a utility’s water resource toolbox. |

In November 1992, Tucson Water began delivering treated Colorado River water to its customers. Overnight, the tap supply for about half the department's customers went from 100 percent groundwater to 100 percent surface water supply. Customers soon began experiencing water quality problems:

• Tap water in many homes and businesses turned brown, yellow, or red.

• Many taste and odor problems were reported.

• The water appeared to damage household appliances by introducing sediment and corroding exposed metal, galvanized steel in particular.

Department staff could account for some of the taste and aesthetic problems. The difference in mineral content between Colorado River water and the average Tucson groundwater was 700 milligrams per liter (mg/L) and 325 mg/L, respectively. Utility staff expected, however, that these anticipated problems would be short-lived as the water and pipes found a new equilibrium. Instead, the complaints continued to grow. Staff tried varying combinations of pH adjustments and corrosion inhibitor levels, but making these adjustments while the treatment plant was on-line further destabilized the water system. System flushing, a standard utility response to water quality issues, loosened existing rust and exposed previously stable corrosion scales to the water.

Public complaints turned into outrage, and people began to worry what effect the corrosive water would have on their "internal plumbing." A portion of the river water delivery area hardest hit by the water quality problems was returned to groundwater in October 1993. In the fall of 1994, state authorities closed the CAP canal system for repairs. Tucson’s mayor and council then directed the department to cease the delivery of Colorado River water until the water quality problems could be resolved. The remaining customers still receiving river water – about one-third of Tucson Water’s customer base -- returned to groundwater service.

In November 1995, voters passed, by a significant margin, a citizen’s initiative prohibiting the direct treatment and delivery of Colorado River water using the existing treatment plant. The treatment plant was taken off line and place in idle-mode.

Try, try again

Tucson Water was forced to "go back to the drawing board" to find an acceptable method of making use of Colorado River water, because the area could not sustain a reliance on groundwater alone. A comprehensive research program based on extensive bench and pilot studies found that because of the unique characteristics of the city’s aging infrastructure and its long-established balance with groundwater, the use of zinc orthophosphate exacerbated the iron uptake from old corrosion scales.

The utility also evaluated several alternative methods of using Colorado River water and eventually chose the Clearwater Program, which reintroduced surface water through a recharge and recovery process. This process uses Soil-Aquifer Treatment (SAT where passage through more than 350 feet of soil takes the place of standard treatment plant filtration, see sidebar). The resulting blend of recharged surface water and native groundwater is recovered and delivered to the drinking water system. The city contracted design work for a large recharge and recovery project west of Tucson on retired agricultural property acquired by the department in the 1970s for the associated water rights.

The customer is right

If the department was going to reintroduce Colorado River water into the community, a lot had to change. There had to be a significant improvement in customer perception of both the water and the utility’s ability to deliver it without the previous problems. To meet this need, Tucson Water developed the “At the Tap” program, which evaluated water quality at the point of use rather than at the treatment plant.

At the Tap featured innovative efforts to restore confidence:

• The first was a series of water taste and odor workshops run by a nationally-recognized customer preference firm. In the fall of 1998, more than 100 representative customers went through a rigorous process during which they tasted various water blends -- from 100 percent river water to 100 percent groundwater -- and determined their preferences. Through this process, which was also demonstrated to government officials and the media, Tucson Water’s customers self-selected a preferred blend of 50 percent recharged Colorado River water and 50 percent groundwater.

• In 1999, the Ambassador Neighborhoods Program enlisted the help of homeowners to prove the utility could deliver the blend safely and without negative effects. Four representative "neighborhoods" of 10 to 25 homes were selected throughout the service area. These homes were isolated from the main water system and supplied with the 50/50 blend that ultimately would be recovered from the Clearwater facility. The program met its mission and customers reported no problems.

• From mid-1999 through May 2001, the department distributed half-liter bottles of the 50/50 blend at community events, shopping mall displays, and through various businesses. Staff also set up 5-gallon bottles at city facilities, such as libraries, neighborhood centers, and parks. This "taste it for yourself" effort required a significant investment in both materials and labor as more than 1 million bottles eventually were distributed over a two-year period.

The program largely restored community confidence in Colorado River water, and customers appreciated the opportunity to guide the utility in the selection of a preferred blend.

A more sustainable option for everyone

The Clearwater facility produces the 50/50 blend and will do so for at least the first 10 years of operation. After that time, the facility will make adjustments slowly to spread the change in water quality over time. This gradual process will provide additional insurance against destabilizing the equilibrium between the water and the mains and private plumbing.

While the recharge and recovery facilities have allowed Tucson to use its renewable supply of Colorado River water, the investment made by customers and the community as a whole was significant. In addition to the original $150 million investment made in the early 1990s, ratepayers have funded a program of nearly $200 million to construct the Clearwater facilities. That investment will grow as Clearwater Phase 2 is constructed several miles south of the existing facility. The recharge basins at Phase 2 will begin accepting Colorado River water in the fall of 2008, and the facility will grow to full-scale recharge (60,000 acre-feet) in 2010. Together, both phases of Clearwater will enable the department to make use of its entire annual Colorado River allocation of 144,000 acre-feet.

Tucson Water and its customers continue to evaluate the fate of the largely unused CAP Treatment Plant. Since it was turned off in 1994, regulations under the Safe Drinking Water Act have continued to evolve. Should the plant be restored to service, significant changes will be necessary to meet requirements and to take advantage of technology improvements. Although the ultimate use of this facility is undefined at this point, it is abundantly clear to Tucson Water that any decisions must involve its customers and the community it serves.

About the Author

Mitchell Basefsky has been the public information officer at Tucson Water since 1995. In 2002, he received the inaugural Public Communications Achievement Award from the American Water Works Association.