Satellites are Exposing Methane Leaks—and It Found a Huge One That’s Raising Eyebrows

The first satellite designed to monitor the planet’s methane leaks is definitely doing its job: a little-known gas well accident in Ohio is reportedly one of the largest methane leaks ever recorded.

Methane: the ambiguous greenhouse gas that almost no one seems to talk about, but the one that is arguably more dangerous—and abundant—than CO2. Methane is more potent than CO2, and scientists expect that as temperatures rise, the relative increase of methane emissions will outpace that of carbon dioxide from various environmental sources affected by climate change.

Why Do we Care About Methane?

Methane emissions comes from a variety of sources, almost all of which are amplified or exasperated by the effects of climate change and human activity. These sources include melting permafrost, microorganisms in freshwater systems, including gas-leaks from oil and mining sites (among other forms of fossil fuel production), agriculture and livestock farming, landfills and waste, biomass burning, rice agriculture, to name a few.

Like carbon dioxide, methane is a natural element that has natural cycles within the atmosphere—but the idea of climate change is the overstressing of these atmospheric compounds that throws natural systems out of whack. Basically, humans are driving climate change by putting too much methane into the atmosphere too quickly, and the Earth can’t keep up.

One major contributor to this methane problem is leaky and unregulated machinery fossil fuel sites; for example, when burned for electricity, natural gas is cleaner than coal and produces about half the carbon dioxide that coal does. But if the methane escapes into the atmosphere before it’s burned properly, it can warm the planet more than 80 times as much as the same amount of carbon dioxide over a 20-year period.

The Satellite

A Dutch-American team of scientists recently published the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences—a new space technology that detects leaks of methane from oil and gas sites in particular.

“We’re entering a new era. With a single observation, a single overpass, we’re able to see plumes of methane coming from large emission sources,” said Ilse Aben, an expert in satellite remote sensing and one of the authors of the new research. “That’s something totally new that we were previously not able to do from space.”

But this technology does not just detect methane—it has already reinforced the view that “methane emissions from oil installations are far more widespread than previously thought,” according to a New York Times article.

It is responsible for pointing to major leaks that are a threat to the environment and public health, and it is a good indicator of just how frequently these leaks are happening around the world.

Ohio Site Blowout

One specific event last year in Ohio is causing some major concerns. An accident in February 2018 at a natural gas well run by an Exxon Mobil subsidiary in Belmont County, Ohio released more methane than the entire oil and gas industries of many nations do in a single year, the research team found. The episode was so bad that about 100 nearby residents within a one-mile radius had to evacuate their homes while workers scrambled to plug the well.

The Exxon subsidiary, XTO Energy, said it could not immediately determine how much gas had leaked at the time. However, the European Space Agency had just launched a satellite with a new monitoring instrument called Tropomi, designed to collect more accurate methane measurements.

The group decided they would investigate to see if it could gather an accurate measure from the Ohio accident. The topic of methane leaks was not new for the natural gas world, and growing scrutiny over the reckless leakage of this colorless, odorless gas gave researchers that much more curiosity to look into the incident. One New York Times article dives into the growing “leak problem” within the natural gas industry.

The satellite’s measurements of the Ohio site showed that in the 20 days it took for Exxon to plug the well, about 120 metric tons of methane an hour were released. That amounted to twice the rate of the largest known methane leak in the United States, from an oil and gas storage facility in Aliso Canyon, California, in 2015 (though that event lasted for longer and had higher overall emissions).

While the Ohio blowout really caused havoc on methane emission levels and public health concerns, researchers said it also was a big indicator that other large leaks could be going undetected.

“When I started working on methane, now about a decade ago, the standard line was: ‘We’ve got it under control. We’re managing it,’” Dr. Hamburg said. “But in fact, they didn’t have the data. They didn’t have it under control, because they didn’t understand what was actually happening. And you can’t manage what you don’t measure.”

Exxon is unsure as to if the satellite readings are an accurate measurement of the methane levels released since Exxon spokesperson, Casey Norton, said the company’s own scientist reviewed images and pressure readings from the well to arrive at a smaller estimate of the emissions from the blowout. Exxon is currently in touch with satellite researchers to sit down and “talk further to understand that discrepancy and see if there’s anything we can learn.”

Methane leaks are actually somewhat common, and they pose a threat to both climate change and human health. Miranda Leppla, head of energy policy at the Ohio Environmental Council said there had been complaints about health issues among Ohio residents closest to the well including irritation, dizziness, and breathing problems.

The Good

The new space satellite collects a significant amount of data every single day. Scientists said that a critical task was how to more quickly sift through tens of millions of data points collected by the satellite to identify methane hot spots on Earth. Studies of oil fields in the US alone have indicated that a small number of sites with high emissions are responsible for a bulk of the methane releases.

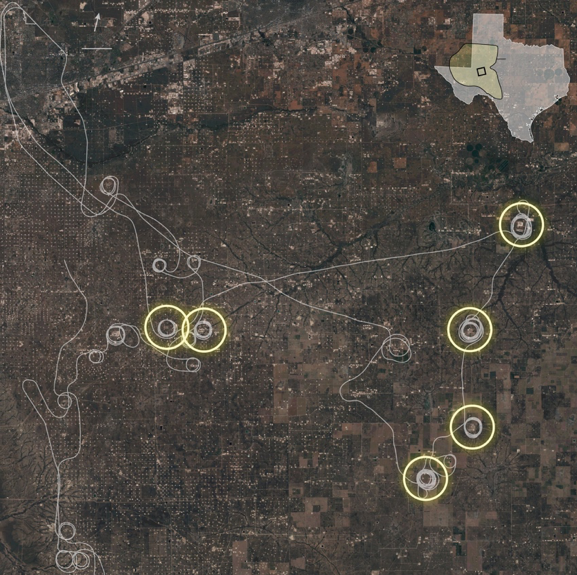

As if the amount of data was not overwhelming enough, methane gas is also essentially invisible. Therefore, scientists need to use expensive aircraft and infrared cameras to make the invisible gas visible. Last week, The New York Times shared a visual investigation with airborne measurement equipment and advanced infrared cameras to expose six “super emitters” in a West Texas oil field.

However, there has already been one case where researchers noticed a large leak from a natural gas compressor in a station in Turmenistan, in Central Asia. Researchers estimated the emissions were extremely high and dangerous, and the leak has since been stopped after they raised alarms through diplomatic channels.

“That’s the strength of satellites. We can look almost everywhere in the world,” said Dr. Aben, a senior scientist at the Dutch space institute in Utrecht and an author on both papers.

Photo from The New York Times article

The Bad

This satellite technology is not foolproof and without cons, though. Satellites cannot see beneath clouds, for example. Plus, scientists must do complex calculations to account for the background methane that already exists in the earth’s atmosphere.

Still, these complications do not undervalue the methane-detection technology scientists are using. Like nearly all technology, this device can always be improved.

The Ugly

There is still a lot more to explore about methane in the atmosphere, the potential contributions and risks, and the commonality of the silent leaks that have been and are still undetected. After all, there are huge environmental and public health consequences to consider.

Dr. Hamburg of the Environmental Defense Fund agrees:

“Right now, you have one-off reports, but we have no estimate globally of how frequently these things happen. Is this a once a year kind of event? Once a week? Once a day? Knowing that will make a big difference in trying to fully understand what the aggregate emissions are from oil and gas.”