Going With the Flow

- By Laura Williams

- Jun 27, 2011

Black ties. Long dresses. A stunning location. It was, according to Kay Ball, a project manager with Louisville Water Company, the Oscars of the engineering world: the American Society of Civil Engineers' OPAL awards, given each March to leading engineers for innovative projects that contribute to people’s well-being and overcome design challenges.

Past winners have included the Statue of Liberty renovations; the Rio-Antirrio Bridge, the world's longest multi-span cable-stayed bridge, which crosses Greece’s Gulf of Corinth; and Washington, D.C.’s Metrorail system. In other words, Ball said, “The judges like the big, sexy projects.”

But this year Ball’s project, a riverbank filtration system housed entirely underground, took home the award, much to the team’s surprise and delight. “Honestly, we were tickled to death,” she said.

Louisville, Ky.'s riverbank filtration system is tiny in comparison to these typical award-winners, in both cost and visibility. It cost only $55 million, about the same as the uber-jumbotron in the mammoth Dallas Cowboys stadium, one of the other contenders for the 2011 ASCE award. The only visible portion of the project is a pump station built on the site of an existing filtration center.

This presented a bit of a problem when the team was gathering materials to submit to ASCE for the awards contest. “We were looking around and thinking, ‘What do we send them a picture of? It’s all below ground,” said David Haas, director of water treatment for Jordan, Jones and Goulding consultants.

They finally settled on a bright image of the pump station’s interior in which its green pipes seem to glow in the sunlight that streams in through the windows.

The impetus for the project, which began in 2007, came from in the company’s search for an effective method to remove microbial constituents from the abundant supply of river water. Runoff from farmers’ fields in the spring, spills on the river, and sediment from floods make their way into the river, causing its quality to fluctuate wildly.

Ball said the utility evaluated various anti-microbial technologies, including membrane filtration, ozone treatment, and UV disinfection, before ultimately settling on riverbank filtration as the best option. “We not only wanted to meet the future regulations, but we also wanted to have good aesthetics of the water. We wanted it to deal with taste and odor issues in addition to anti-microbial ones,” Ball said. “We wanted it to do everything, and so, bottom line, that’s why we went with riverbank filtration.”

The first incarnation of the filtration system installed a brick-trimmed pump and power station on the side of the Ohio River near a copse of trees. The upward suction from the pump drew river water through the natural layers of sand and sediment in the riverbank, which acted as a natural filter, and into a series of collector wells that radiated out from a large-diameter caisson.

But the community wasn’t happy with the obstructed view of the river. “There was a huge pump station, and even though we added a lot of architectural elements to make it aesthetically pleasing, … it became apparent early on that the public was not going to accept a huge, 60-foot power and pump station, regardless of how pretty it looks,” Ball said.

Furthermore, the plan called for the construction of 15 to 20 additional stations, which would make it hard for community members to escape these masonry eyesores.

So Ball and other team members at the Louisville Water Company got to work brainstorming ideas on how to transport the water from the river across several miles to the filtration center without marring the landscape and intruding on the community’s enjoyment of the river. “It was almost in jest one day that we said, ‘Well, what if we built a tunnel?’” Ball said. “And when we stopped and thought about it for a minute, we said, ’Well, you know, that’s not so far-fetched.’”

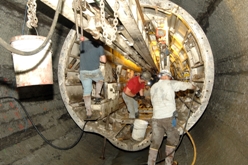

So they called up Haas’ company, which specializes in tunneling, and together they came up with a design in which gravity causes groundwater and river water to drain into the collector wells. Those collector wells feed into the caisson, which drains into a mile-and-a-half-long tunnel leading to a pump station built within the grounds of the in the existing filtration plant.

“Essentially, we took well-established collector well technology and combined it with well-established tunneling technology,” Haas said. “We took the two technologies and put them together for the first time to yield a project with broad-based community support.”

The team designed the tunnel so that the Louisville Water Company could extend it if officials decide to convert the utility's other water treatment plant into a gravity-fed enterprise or if it wants to add another collection point. They agreed that the most challenging part of the project was ensuring the tunnel aligned with the drainage hole in the caisson.

“When we went to connect the two, it was very comforting to see the tunnel was actually where it was supposed to be,” joked Henry Hunt, a senior project manager at Ranney Collector Wells, which built and installed the wells.

The project finished up in December of 2010, and Ball said that in addition to getting a thumbs-up from the community, it improved the quality of the water coming into the treatment plant. This puts less wear on the plant’s equipment and has pleased the plant’s operators, who now have to vary the treatment regimen only slightly from day to day because of the consistent quality of the incoming water. Using the riverbank gravel and sand as a filter prevents the scourge of Zebra Mussels and other small animals blocking intake pipes. An added bonus is that, because it mixes with some groundwater, the incoming water hovers at the about same temperature year-round, which Ball anticipates will diminish water main breaks in the winter. Key in all of this, however, is the community support for the project.

“The magic with all this is that it met all the environmental objectives, it met the quality objectives, and it met the community objectives,” Haas said.

Want to see more pictures of the Louisville Water Company’s riverbank filtration system? Check out the album on our Facebook page.