Snakes in the Glades

Researchers implant a radio transmitter in a 16-foot, 155-pound female Burmese python (Python molurus) at the South Florida Research Center, Everglades National Park. Photo courtesy of Lori Oberhofer, National Park Service.

Five giant non-native snake species would pose high risks to the health of ecosystems in the United States should they become established here, according to a U.S. Geological Survey report released on Tuesday.

The report, "Giant Constrictors: Biological and Management Profiles and an Establishment Risk Assessment for Nine Large Species of Pythons, Anacondas, and the Boa Constrictor," details the risks of nine non-native boa, anaconda and python species that are invasive or potentially invasive in the United States. Because all nine species share characteristics associated with greater risks, none was found to be a low ecological risk. Two of these species are documented as reproducing in the wild in South Florida, with population estimates for Burmese pythons in the tens of thousands.

Based on the biology and known natural history of the giant constrictors, individuals of some species may also pose a small risk to people, although most snakes would not be large enough to consider a person as suitable prey. Mature individuals of the largest species—Burmese, reticulated, and northern and southern African pythons—have been documented as attacking and killing people in the wild in their native range, though such unprovoked attacks appear to be quite rare, the report authors wrote. The snake most associated with unprovoked human fatalities in the wild is the reticulated python. The situation with human risk is similar to that experienced with alligators: attacks in the wild are improbable but possible.

High-risk species—Burmese pythons, northern and southern African pythons, boa constrictors and yellow anacondas—put larger portions of the U.S. mainland at risk, constitute a greater ecological threat, or are more common in trade and commerce. Medium-risk species—reticulated python, Deschauensee’s anaconda, green anaconda and Beni anaconda—constitute lesser threats in these areas, but still are potentially serious threats.

The USGS scientists who authored the report emphasized that native U.S. birds, mammals, and reptiles in areas of potential invasion have never had to deal with huge predatory snakes before—individuals of the largest three species reach lengths of more than 20 feet and upwards of 200 pounds.

The report notes that there are no control tools yet that seem adequate for eradicating an established population of giant snakes once they have spread over a large area. Making the task of eradication more difficult is that in the wild these snakes are extremely difficult to find since their camouflaged coloration enables them to blend in well with their surroundings.

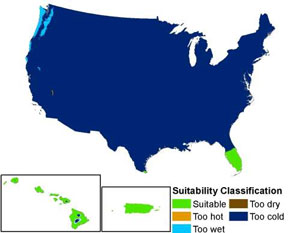

USGS researchers forecasted the areas of the country most at risk of invasion by these giant snakes. Based on climate alone, many of the species would be limited to the warmest areas of the United States, including parts of Florida, extreme south Texas, Hawaii, and America’s tropical islands, such as Puerto Rico, Guam, and other Pacific islands. For a few species, however, larger areas of the continental United States appear to exhibit suitable climatic conditions.

The Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Park Service will use the report to assist in further development of management actions concerning the snakes when and where these species appear in the wild. In addition, the risk assessment will provide current, science-based information for management authorities to evaluate prospective regulations that might prevent further colonization of the U.S. by these snakes. The 300-page report provides a comprehensive review of the biology of these species as well as the risk assessment.